Sometimes, all the stars seem to align, and you find yourself saying Thank you, oh Mighty Odin. When I launched this challenge – to myself – I had no idea how many questions I’d get, nor whether I’d be knowledgeable enough to reply to them, nor whether I’d be remotely successful in bringing useful and verified information to those who asked them. I was, therefore, very pleasantly surprised, when I found that not only there were several questions, but also that I had the capacity to reply to them. To this question, in particular, I have an extra boon, because I’ve actually been working some of these subjects during my PhD (do feel free to imagine me doing a #success Meme face).

I will be replying to this question more than Odin will, because it is directly asked to me and is questioning my beliefs as a Historian. Without further ado, let’s sink into the issue.

Do you believe in the possibility of an ancient underwater building or city since the Romans had developed concrete that wouldn’t deteriorate in water?

Yes. Because we have ancient underwater cities.

For matters of practicality, I’m going to divide this reply into three parts. Firstly, I’m going to explain what this concrete actually was, how it was made, and how and where it might have been originally used in underwater contexts.

1- Hydraulic Concrete

Romans did, in fact, develop concrete that did not easily deteriorate in water. In Latin, this was called opus caementicium, and it was made in a very specific way: it combined the use of a volcanic ash, called pozzolana, with diverse types of aggregate (thus, sands or stone). This pozzolana, when mixed with aggregate, was applied to construction and left to settle, thus creating an extremely hard and very functional concrete which, the Romans soon found, could easily be used in salt water without presenting significant degrees of deterioration.

This type of concrete, however, was a relatively late discovery in the Roman world. Without entering discussions about the effective levels of settlement in the area throughout Prehistoric times, the legendary birth of Rome is set to the 8th century BCE (to be exact, 753 BCE); this type of hydraulic concrete did not appear until much later, about the 2nd century BCE, thus, at least, 600 years afterwards. It also follows that its main period of implementation as a construction material was not until the 1st century BCE.

To give you some degree of comparison, Petra (in modern-day Jordan) was made around 1200 BCE, the Parthenon in Athens about 440 BCE (give or take a few years), and the Colosseum in Rome between the years of 70 and 80 of our era (CE). Thus, the invention of this very specific type of hydraulic concrete is closer in time to the days of Julius Caesar than to the early days of Rome.

This new, useful material was, of course, utilised above the sea-surface: one noticeable example is the dome of the Roman Pantheon, which survived to these days and may still be visited. But one of its main uses, and this brings us to the matter of underwater construction, was in harbours. All throughout the Mediterranean, there are harbours “born and raised” throughout this 1st century BCE. Hydraulic concrete was most likely first used around the region of Puteoli (the volcanic ash comes from this specific place, after all), but it soon spread to other harbours distant from the Italian Peninsula. Seeing that it was a material that could easily survive underwater, it makes perfect sense that one of its main places of application was in ancient harbours, of which one of the most well-known is that of Caesarea Maritima, developed by Rome and King Herod the Great in circa 30 BCE. There were specific techniques which involved using wooden stakes to help the cement settle in place, something which took, in average, about two-months; one single mistake would have been terribly hard to correct after it was settled, as one might imagine, and therefore, Roman engineers devised methods to make the application safe and practical. Hence, as far as building underwater with this concrete goes, this is the most evident archaeological evidence we have.

Roman Pantheon. Photo from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rome_Pantheon_front.jpg, by Roberta Dragan.

However, I did say there are underwater cities. This will lead us to part two.

2- Sunken cities

The planet is hardly static, and cities built around the coastline are sometimes prone to disappearing. This is caused, most generally, by earthquakes, which may change the coastline and allow for water level rises; by the natural rising and falling of seawater levels through the centuries (there can be rather significant differences!); or by other natural phenomena, such as storm surges, coastal floods and wave action. Therefore, a bit all over the world, you have plenty of examples of cities which, for one reason or another, now lie in the depths of the sea and the ocean. Some have been the object of archaeological works, others have not. Some can even be visited by scuba divers. Pictures of these cities are always stunning to see.

Was Roman concrete used in all of them? No. Although it is a lot more durable underwater than many of its modern derivates, fact is that underwater cities have been found not only all around the world (thus, in places that had no access to this concrete and never even dreamed it existed), but also that were built (and likely sunken) long before Roman concrete was invented, or long after it had stopped being used. Some examples:

- Palovpetri, modern-day Greece. This city was inhabited between the 3rd millenia BCE and the middle of the second millenia; on the turn to the first millenia, it would have been sunken by several earthquakes.

- Herakleion, in modern-day Egypt. This used to be an important trading harbour for the region, and it is mentioned in the writings of Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century BCE; its, in all likelihood, go way further back. Later, during the 2nd century BCE, several of these natural phenomena led to it slowly being overtaken by the sea.

- Dwarka, modern-day India. Founded before the year of 574 of our time – some of the materials found, according to the Mahabharata Research, are over 7500 years old. They’re unsure why it is underwater, but it is most likely due to sea-level rises or an earthquake – which led to sea-level rises, or a change of the sea-bed.

- Port Royal, Jamaica. It was founded in 1494, and it suffered an earthquake and tsunami in 1692, never returning to its original state.

These are only five, but there are thousands, from the American Continent to the United Kingdom to China, and you can spend many hours just looking at the beautiful underwater artefacts and structures that have been photographed.

3- How about Atlantis?

I think that fascination about underwater cities, aside from how beautiful they naturally look, the many archaeological records they can bring us, and the fact that it’s super exciting to suddenly find a 3000 year-old city that no-one even knew existed, is partly derived from the myth of Atlantis. The myth itself, as it is known in the Western world, was first mentioned by Plato, a philosopher who lived in the 5th Century BCE.

Atlantis appears in two different works. The first is Timaeus, a work that takes the shape of a dialogue between a character named Timaeus of Locri, Socrates, Hermocrates and Critias. They’re basically discussing the Ideal State (politically speaking), and Atlantis first appears as an allegory:

The second mention of Atlantis is in Critias, a work of a similar nature, which follows a dialogue between Critias and other characters:

The source proceeds, describing those early years of the foundation of the city, its geography, fountains, fertility, plains, even the Royal Palace; you can read all of that in the original book, which is linked to below. Then their laws and their application, the military, the way its king could act. And it ends thus:

Behold, therefore, Atlantis, a city who had everything and lost everything due to their hybris, their arrogance. It’s really interesting how the source says that things started taking the wrong turn “when the divine portion began to fade away (…) and the human nature got the upper hand”, and that “they appeared glorious and blessed at the very time when they were full of avarice and unrighteous power”.

Much has been said about Atlantis, and much has been made of the debate about whether it is real or an allegory. One of the perspectives is that Atlantis is entirely fictional and an allegory created by Plato as a narrative device. As Harold Tarrant says in a 2007 article, «human beings, it seems, have a natural need for myth», and in particular to explain the «beginnings» and the «ends» of things. As Tarrant goes on to say, people in Antiquity often considered it a myth themselves. This seems demotivating for those who hope for a massive archaeological discovery.

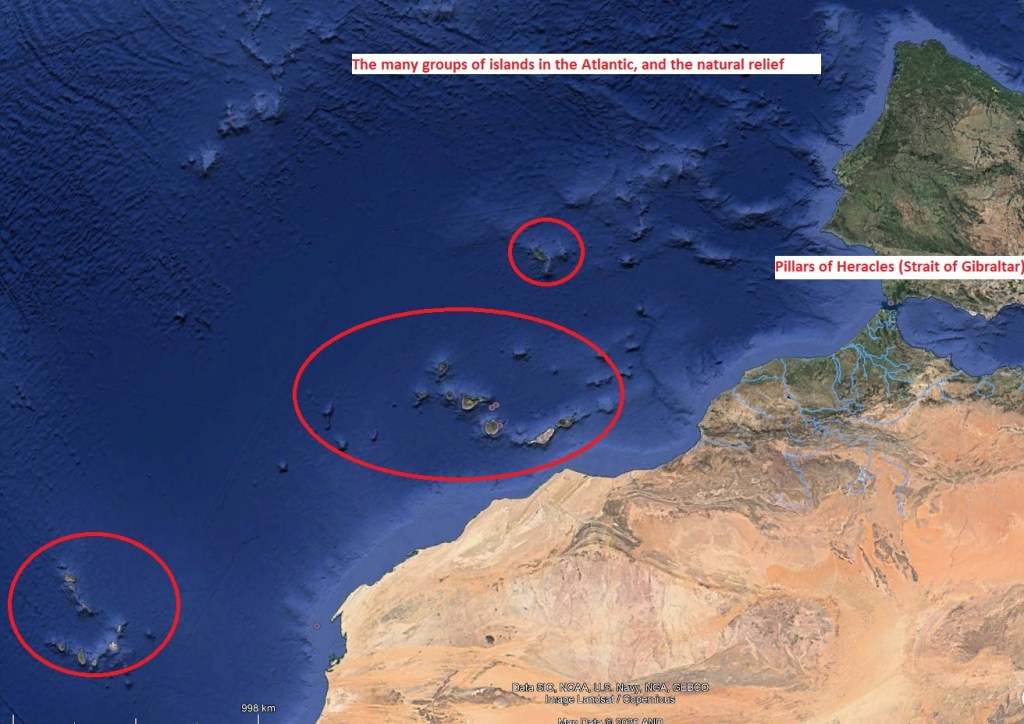

However, there are other perspectives, some which have taken it seriously and have tried to find the island in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Some of the most popular are:

- Knossos, in Crete. The Minoans were a very advanced civilization which suddenly collapsed due to, most likely, a cataclysmic earthquake.

- Sardinia and Malta, or even Troy.

- The Azores Islands.

- The Canary Islands.

- The Island of Madeira.

- Cape Verde.

Archaeology often takes the search seriously. Eric Cline says that we’ve already found Atlantis: in 2017, he affirmed that «if there is any kernel of truth underling the myth of Atlantis at all» (notice the doubt, always lingering, always present», it is most likely the Greek Island of Thera, which suffered a volcanic eruption during the 2nd millennium of the BCE.

As you see, there are thousands of hypotheses regarding whether a possible Atlantis might be; there are also many more thousands of scientists who believe it is but a myth, created to explore the idea of a civilisation who grew so arrogant that it was punished by the gods – or to remind us that even the greatest civilisations can suddenly crumble under the influence of factors they cannot control. But the question was directed to me, directly; whether I believe in it. Well, the Spanish have a saying: Yo no creo en brujas, pero que las hay, las hay, which, roughly translated, means: I do not believe in witches; however, that they exist, they do. I personally see Atlantis as a myth, and do not currently believe it was an actual civilisation nor place. I do believe, however, that collective memory of cataclysms (such as the major volcanic eruptions both in Knossos and Thera) may have influenced these thoughts and ideas, and that if Atlantis was not real, the idea behind Atlantis may well have been. It just suffered a slight revamp under Plato’s hands. There is also one last thing: it is very often the case that things that Historians and Archaeologists dismiss as myths (whether cities, people, artifacts… you get the idea!) often end up being proven real by archaeological records. Perhaps Atlantis is just a myth. Perhaps Atlantis was a real location, and we just don’t have the means to find it yet. Who knows? All I say is, never say never.

Sources:

Roman concrete:

Amato, Lucio and C. Gialanella. 2013. “New evidences of the Phlegraean bradyseism in the area of Puteolis harbour”. In Geotechnical Engineering for the Preservation of Monuments and Historic sites, ed. Emilio Bilotta, Alessandro Flora, Stefania Lirer and Carlo Viggiani, 137-43. London: CRC Press / Taylor & Francis Group. Link: http://www.ancientportsantiques.com/wp-content/uploads/Documents/PLACES/ItalyWest/Pozzuoli-Amato2013.pdf

Jackson, Marie, Dalibor Všianský, Gabriele Vola and John Peter Oleson. 2012. “Cement Microstructures and Durability in Ancient Roman Seawater Concretes”. In RILEM Book Series. Vol. 7, 49-76. New York: Springer.

Keay, Simon. 2012. “The port system of Imperial Rome”. In Rome, Portus and the Mediterranean, 33-67. London: The British School at Rome.

Noli, Alberto and Leopoldo Franco. 2009. “The Ancient Ports of Rome: New Insights from Engineers”. Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea: An International Journal on Underwater Archaeology 6: 189-208.

Oleson, John Peter, Christopher Brandon, E. Gotti, Luca Gottalico, Roberto Cucitore and Robert L. Hohlfelder. 2006. “Reproducing a Roman Maritime structure with Vitruvian pozzolanic concrete”. Journal of Roman Archaeology 19(1): 29-52.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288091092_Reproducing_a_Roman_Maritime_structure_with_Vitruvian_pozzolanic_concrete

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_concrete

And, well, me, but my PhD thesis hasn’t been published yet! 😀

Underwater cities:

http://mahabharata-research.com/about%20the%20epic/the%20lost%20city%20of%20dwarka.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarka

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavlopetri

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Royal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heracleion

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427361-700-pavlopetri-greece/

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20427361-800-dunwich-uk/

https://www.newscientist.com/round-up/drowned-cities-myths-secrets-of-the-deep/

https://www.newscientist.com/round-up/drowned-cities-myths-secrets-of-the-deep/

https://in.musafir.com/Blog/6-submerged-cities-around-the-world.aspx

http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20190228-athens-bizarre-underground-phenomenon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaymakli_Underground_City

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derinkuyu_underground_city

https://www.history.com/news/8-mysterious-underground-cities

https://www.travel-ancient-world-sites.com/Historical-Timeline.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheon,_Rome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesarea_Maritima

Atlantis:

Tarrant, Harold. 2007. “Atlantis: Myths, Ancient and Modern.” The European Legacy – Toward New Paradigms, 12(2), 159-172.

Cline, Eric. 2017. “Finding Atlantis?” Three Stones Make a Wall: The Story of Archaeology. (pp. 146-156). PRINCETON; OXFORD: Princeton University Press.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Location_hypotheses_of_Atlantis

Plato, Critias: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/critias.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critias_(dialogue)

Plato, Timaeus: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/timaeus.html