His Majesty the Odin and The Chronicler have once more teamed up to bring answers to your questions. This time, we’re getting into the immensely cool and often elusive world of Ancient Art, namely, Greek sculpture. Two questions were posed to us, and to those questions we will try to reply, to the best of our capacities. However, before we start replying to these questions, there’s an important matter that Odin specifically asked me to talk about. This is something that has been generally divulged in the past few years, but as it is a relatively recent discovery and it hasn’t reached everyone just yet, Odin felt it was important for it to be shared, first and foremost.

Did you know that Ancient Greek Sculptures were painted?

That’s right. Whiteish marbles are a Renaissance and Neoclassical trend. Greek and Roman marble statues were usually painted, and some of them were actually found with some traces of that age-old paint; for most of them, however, the paint ended up being washed off and gave the false illusion of the pale marbles we are so familiar with. There are a few reliable articles where you can find some samples and even samples of what they must have originally looked like:

https://edu.rsc.org/resources/were-ancient-greek-statues-white-or-coloured/1639.article

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/29/the-myth-of-whiteness-in-classical-sculpture (I love this title)

This is called polychromy. Painted statues have actually been going on for centuries, and you can see plenty, for instance, in Dutch and Portuguese Medieval and Early Modern sculptures, particularly wooden sculptures. Of course, when you look at the colourful images, they may not seem as elegant as the pale marbles we’re used to. Why did they paint them? Well, statues are objects of worship, first and foremost. In the Ancient World, there is plenty that can be said about a statue. If anything, because, in their myths, statues may come alive. You only need to look at the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea. The Greek Gods (and Roman, and Egyptian, and most Gods in the Ancient world, for that matter) are ever-traveling entities that can show up at any place, at any time: legend has it that when Mithridates besieged Rhodes during the First Mithridatic War, a vision of Isis would have launched fire against his sambucas (a war machine).

Deborah Steiner has a very interesting chapter name in her book about Ancient Greek statues (see Sources below): she calls it Replacing the Absent. That is, first and foremost, the role of a statue: she goes on to explain that, at first, they represented and replaced the dead, especially in cases of absent corpses, so that the spirit can rest. They can also be created as offerings and ways to thank or appease divinity. First and foremost when we’re speaking of Ancient Gods, they’re eidolons, figures to be object of reverence, to be used in rituals and processions if need be. Greek sculptures are attempting to represent a subject, and therefore, when they present a subject such as divinity, they will present it in colour, as the Gods are made to be a perfected physical image, to represent a certain «attribute» or «value» (Zaidman and Pantel): the Greek Gods are made to look as humans, not because they believed they were exactly like so, but because they were trying to represent physical perfection». And if they’re trying to emulate an expression of absolute physical beauty, they represent it in an anthropomorphic, human-like figure which, as all human figures, has some colour – coloured eyes, coloured hair, coloured skin. Even in literature, the Greek Gods are not marble-like figures moving along: most goddesses and god-like women are envisioned as fair-haired, as it was the beauty ideal en vogue at the time.

In this regard, Steiner quotes Socrates: painting is «a representation of things seen», and colours are part of that representation; art must not copy, but perfect and beautify. One of the most well-known Greek statues, for instance, goes as far as to use noble materials – the chryselephantine (made in marble and ivory) statue of Goddess Athena, which once stood in the Parthenon and disappeared without much of a trace (see Boardman, 1985), and was decorated with details in actual gold.

While an actor was performing a play, he was believed to incarnate the spirit of god Dionysus. In the same way, a statue could incarnate the spirit of a God. As say Zaidman and Pantel, «The special characteristic of all religious representation is to endow the divinity being figured with a presence without obscuring the fact that it’s not actually there». Statues are an expression of the divine, for which, as the same Zaidman and Pantel said, the Greeks had different words; but, all in all, it is all a bit of the same. These statues could be dressed and bathed, or just rest within the temples (still Zaidman and Pantel); what they were not, was a type of Michelangelo.

Therefore, and going back to Boardman:

- «Hair, eyes, lips and dress were certainly painted on Classical marbles, and we are only less sure about whether or how often flesh parts might also have been tinted (sunburned men and gods, pale women and goddesses)»; weaponry may have also been painted.

- «We too readily project into Classical antiquity expectations about marble sculpture which have been formed by the practices of Renaissance and Neo-Classical artists, who saw Greek sculpture in polished Roman versions, stripped by time of any paint or accoutrements which might sully the pristine, breathing white.»

- There is also the case of the acrolithic, a mixture of wood and marble sculptures, where the flesh (hands, feet and head) would be attached to a wooden body.

- Other materials applied to statues would be «glass or stone», «ruddy copper or silver».

I’ve mostly focused on statues of Gods and demi-gods, which are a significant part of Greek Sculpture, but there were also other types of representations, such as the young men representing athletes (the kouros, singular). Greek sculpture is by no means uniform – there are regional variations, as diverse as the several city-states, and there is an evolution from the most archaic periods until the Hellenistic. Art is not motionless and it keeps developing. But the point is, during the Classical period, and without trying to make a treaty on the symbolism of Greek Sculpture (that would be an endless knot!), most statues were painted, and this happened not only for aesthetical reasons, but also for the purpose of better representing an incarnation of whatever the artist was trying to represent.

Many Greek statues weren’t really marble.

Although the Ancient Greeks did work their statues in marble, the main material for most works is bronze. What we see nowadays, in many cases, are copies of bronze originals which have been destroyed later on, as bronze is a valuable metal which might be a lot more useful to practical people in the shape of, say, a few coins. Thankfully for us, we can have some idea of the original because of the many artists who copied these bronzes and sculpted them into stone. The Romans are responsible for many of these copies. We were also fortunate enough to get some bronze originals, although these exist in a far smaller number than their marble counterparts

When did these bronze statues begin being melted? Well, whenever it was necessary. In William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, he gives us some idea: firstly, during the reigns of Constantine and Theodosius, a time in which Christianity began to settle as the main religion of the Roman Empire and which led to the destruction of figures of the formerly worshiped pagan gods. However, Smith goes on to say that these early years of Christianity in the Roman Empire were by no means the main responsible by the destruction of these works of art, but that the «circumstances and calamities of the times» were the major issue, and that melting bronze statues occurred in «times of need». He poses the main moment of destruction in the 13th century siege of Constantinople, and that this was partly due to the need of collecting bronze. Many of these statues must have been taken to Constantinople upon the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and there they remained until the Crusades came. As said by Dawkins:

«When the capital of the roman world was transferred from Rome to Byzantium, the emperors decorated the new capital with treasures of art from all the cities of Greece, and these remained in their places, naturally with certain losses, due for the most part to fires and earthquakes, but without any very serious diminution, until the warriors of the Fourth Crusade, diverted from the Holy Land, came to Constantinople, took the still virgin city, sacked it, and shattered or melted down almost all the priceless works of antiquity.»

There is also another detail, which can be interpreted, according to Anthony Cutler:

«More certainly he [Niketas] knew older historians’ reports of the Vandal appropriation of Roman bronzes and of the fate of those few statues that remained, melted down by the emperor Avitus for coin to pay his troops».

To strengthen the argument that Niketas was aware of the sacking of Roman treasures by the Vandals, Cutler makes mention of Procopius, History of Wars:

And Gizeric, for no other reason than that he suspected that much money would come to him, set sail for Italy with a great fleet. And going up to Rome, since no one stood in his way, he took possession of the palace. Now while Maximus was trying to flee, the Romans threw stones at him and killed him, and they cut off his head and each of his other members and divided them among themselves. But Gizeric took Eudoxia captive, together with Eudocia and Placidia, the children of herself and Valentinian, and placing an exceedingly great amount of gold and other imperial treasure in his ships sailed to Carthage, having spared neither bronze nor anything else whatsoever in the palace. He plundered also the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, and tore off half of the roof. Now this roof was of bronze of the finest quality, and since gold was laid over it exceedingly thick, it shone as a magnificent and wonderful spectacle. But of the ships with Gizeric, one, which was bearing the statues, was lost, they say, but with all the others the Vandals reached port in the harbour of Carthage. Gizeric then married Eudocia to Honoric, the elder of his sons; but the other of the two women, being the wife of Olybrius, a most distinguished man in the Roman senate, he sent to Byzantium together with her mother, Eudoxia, at the request of the emperor. Now the power of the East had by now fallen to Leon, who had been set in this position by Aspar, since Marcian had already passed from the world. [457 A.D.]

This Gizeric, or Geiseric, was the King of the Vandals and the Alans, who established a Kingdom in the 5th century BCE and plundered the city of Rome herself in the year of 455. Listen, many of these statues were made over 2300 years ago. There have been many situations in which bronze would have been a lot more useful in other forms, however much the statues were, in fact, beautiful. It is an invaluable loss, but we can’t really blame these fellows for trying to make a living in a time during which the world seemed about to collapse! (Yes. We still blame them. Cursed be thee, Geiseric.) All this was just to make a small point: although there were plenty of Greek statues made in marble (even with other materials in the mix), there was a great deal of them that was made in bronze; there were even bronze copies circulating in the Roman Empire and being made during the Roman Empire; some of the bronze originals even survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but most of them did not survive the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

If you look at Robert de Clari, a Medieval source who talks on the Fourth Crusade and the attack to Constantinople, you realise that the crusaders had some issues to pay for the navy they had hired from the Venetian doge. It was therefore agreed that the 36 000 marks they could not pay would be taken from «their part of the first conquests which we make», if the Venetian navy agreed to carry the crusaders across the sea. It is likely thatp art of this payment was made through the many riches found in Constantinople, amidst which – you guessed right – were the original Greek bronzes.

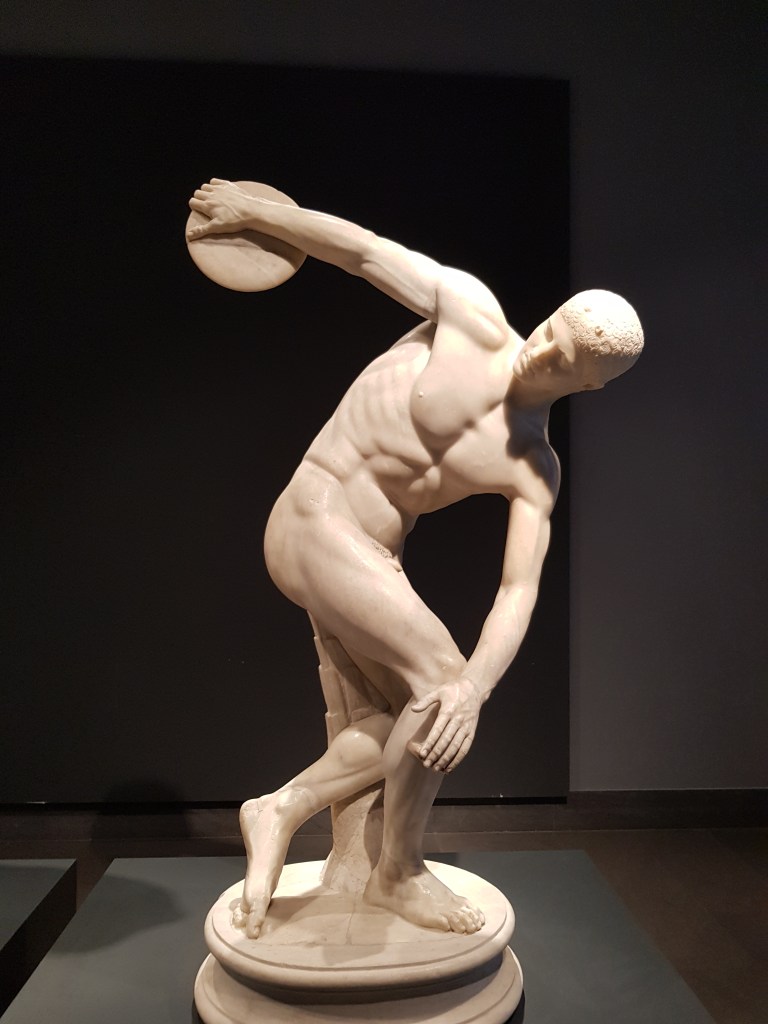

Therefore, when you’re looking at some ancient marble statue, do some quick googling: odds are that you’re not looking at an original. One of the most noticeable cases (and my all-time favourite) is the Discobolus of Myron. Fine, this is not the original, but the replica is pretty awesome in itself. Don’t you think so?

SourceS:

Niketas Choniates, a 12th century historian who lived in Constantinople. https://archive.org/details/o-city-of-byzantium-annals-of-niketas-choniates-ttranslated-by-harry-j-magoulias-1984/page/n409/mode/2up/search/bronze

Geoffrey de Villehardouin, a 13th century chronicler, writing on the Fourth Crusade: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/villehardouin.asp?fbclid=IwAR37VdZ0cCtnbiyzl9MXm-qLkOMHR2N5SAKSh4usa0cnlOpC0dLiOufY-3Y

Robert de Clari, another medieval source on the sacking of Constantinople: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/clari1.asp?fbclid=IwAR2Fv4IDmlfjoA_AutLXoJado7e6etlaa1ifT8nIJVPSocdOMFqIOz7frI8

John Boardman, 1985, Greek Sculpture – The Classical Period.

J. D. Beazley and Bernard Ashmole, Greek Sculpture and Painting to the End of the Hellenistic Period, 1966, Cambridge University Press.

Richard Neer, The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture. 2010, The University of Chicago Press.

Several authors, ed. Roberta Panzanelli: The Color of Life: Polychromy in the Sculpture from Antiquity to the Present, 2008.

James Freeman Clarke, 2019. Ten Great Religions: An Essay in Comparative Theology.

Michael Rice, 1998, The Power of the Bull, Routledge.

Deborah Steiner, 2001, Images in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought, Princeton University Press.

Louise Bruit Zaidman and Pauline Schmitt Pantel, 1989, Religion Grecque, Cambridge University Press.

Helmut Kyrieleis, “Samos and Some Aspects of Archaic Greek Bronze Casting”, Small Bronze Sculpture from the Ancient World.

William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

Anthony Cutler, “The De Signis of Nicetas Choniates. A Reappraisal”, American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 72, No. 2 (Apr., 1968), pp. 113-118

R. M. Dawkins, “Ancient Statues in Mediaeval Constantinople”, Folklore Vol. 35 no. 3, 1924.

Procopius: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/History_of_the_Wars/Book_III#V

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaiseric – On Gaiseric