In the last post about Greek Sculpture, we talked about a huge number of things. The one thing we did not talk about was the actual replies to the questions Odin received! Alas, the Chronicler has digressed amidst other subjects and got lost in the depths of Grecian Art and ancient myths… But we’re here now, and more than ready to finally pose a reply to your questions.

First one:

Where were the Greeks able to source the marble for statues?

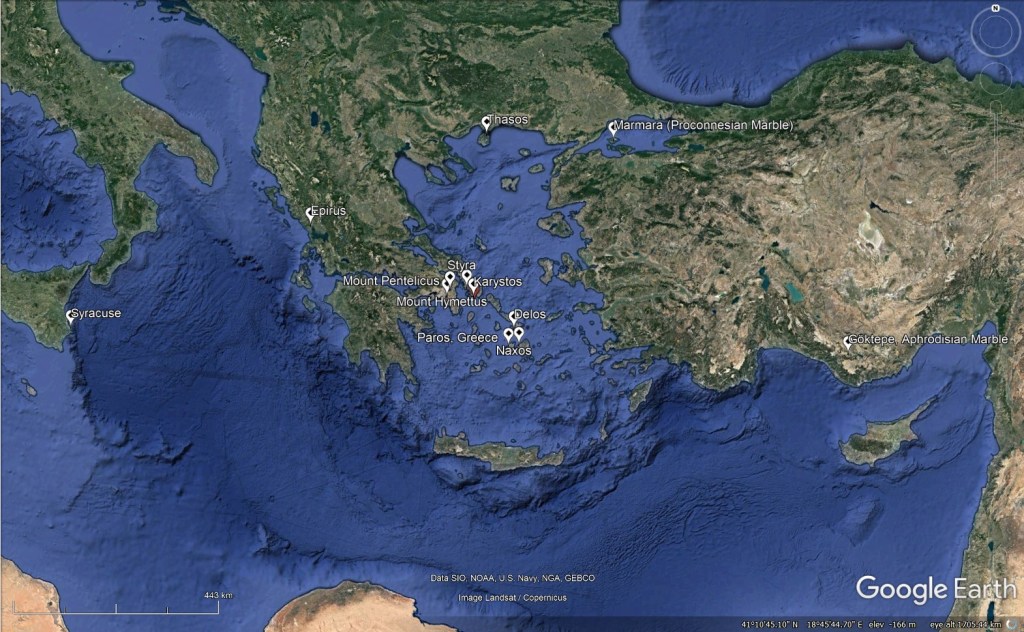

Quarries were developed a bit all over the Mediterranean world, to explore different types of materials. Marble quarries were one amidst many others. Some of them are actually still in work, with marble being extracted for modern buildings and art pieces! In fact, marble has been exploited since long before the Greeks started using it for statues – at least since the Neolithic period. In the Greek World, it was found a bit all throughout Greece and Turkey, with many of them being born of local needs (if you need materials, you create a place for extraction). Some of the most well-known types of marble used in Ancient Greece are:

- Pentelic Marble (from Mount Pentelicus)

- Parian Marble (from the island of Paros)

- Syracuse

- Naxos

- Delos

- Mount Hymettus

- Epirus

- Styra

More frequent in Roman chronologies: - Proconnesian Marble (Island of Marmara)

- Aphrodisian Marble (Göktepe)

- Thasian marble

Looking at the map above, you can see some (although by no means all) of the locations from which marble was extracted. The stone has different characteristics, varying amidst white, grey and pinkish hues. As I said, marble had been worked long before the Greeks: according to Getty Musem’s catalogue on Ancient Marbles, the first big boost happened in the Cycladic islands during the third millennium BCE; then, the big place for marble works will become Crete (Knossos). As time went by, it then extended to other large centres, such as «Myceneae, Pylos, and Athens», all this happening long before Classical and Hellenistic Greece came to life.

What would they do with it if they messed up and had to start over?

Now, the pieces where the marble was worked were an entirely different thing. However, the two most-coveted were, most likely, the first two: Pentelic Marble and Parian Marble. John Boardman, once again, gives some help in this regard: he explains that the Greeks started working marble a lot more than limestone (which is softer and easier to work with) around the 5th century BCE, and they started developing the techniques necessary to work harder stones. As one might imagine, it took quite a few years to become a noteworthy artisan, and the names of many of the apprentices have never reached us. When you reach a certain level of expertise, you will not be as prone to making mistakes as you were in your youth, when you spend your years in practice; then, the method in use was one to make it as error-proof as possible: the Ancient Greeks would draw the general shape of the statue on all sides of the marble, and they would sculpture a bit from each side and rotate. However, we are all humans, and humans are fallible, so we all make a mess, even when we’re very good at something.

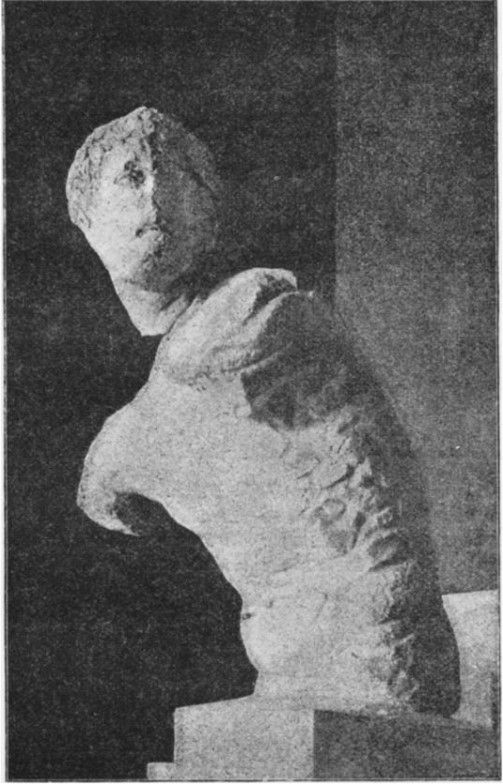

Proof is, there are several examples of unfinished statues. In the late 19th century, E. A. Gardner spoke of several of these unfinished sculptures which were housed in the National Museum of Athens; more mentions of unfinished statues are found in Sources below. There were many reasons why an ancient sculptor might abandon a work: perhaps, as Gardner suggested, he decided that the proportions would turn out all wrong; perhaps the person who ordered the statue decided it would not be convenient to actually pay for it; perhaps the city was hastily abandoned due to war (an example shown by Kenneth Lapatin, namely the statue of Zeus for the Megarian Olympieion). The thing about working such a hard material as marble is that if you make a mistake, it will be difficult to correct. If it was a smaller mistake, the creator might have been able to disguise it, although it is unlikely that the patron would have purchased an imperfect statue. The most likely thing is that mistakes led to the abandonment of the sculpture altogether. What they did to these abandoned sculptures, we do not know for sure; the fact is that many of them reached our days untouched, which means that at least a portion of them wouldn’t have been destroyed. They were purely and simply abandoned, which might sound sad, but if they hadn’t been, we wouldn’t have invaluable clues on the actual sculpting method and the stages of creating an Ancient Greek marble sculpture.

Sources for quarries and ancient marble exploration:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Greece and Rome, edited by John P. O’Neill, 1987.

Henry Washington, “The Identification of the Marbles Used in Greek Sculpture”, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 1-2, 1898.

Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, edited by Nigel Wilson, 2006. Routledge.

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Volume 1. 2010.

Several authors, Marble: Art Historical and Scientific Perspectives on Ancient Sculpture, J. Paul Getty Museum.

Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, edited by Norman Herz, Springer.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, The History of Ancient Art, Volume 1, 1856

Ben Russel, 2013, The Economics of the Roman Stone Trade, Oxford University Press

K. Laskaridis, 2004. “Greek marble through the ages: an overview of geology and the today stone sector”, Dimension Stone 2004. New Perspectives for a Traditional Building Material, A. A. Balkema.

Donato Attanasio, Matthias Bruno, Walter Prochaska and Alì Bahadir Yavuz, “APHRODISIAN MARBLE FROM THE GÖKTEPE QUARRIES: THE LITTLE BARBARIANS, ROMAN COPIES FROM THE ATTALID DEDICATION IN ATHENS.” Papers of the British School at Rome 80 (2012): 65-87.

On marble types: https://www.miningreece.com/mining-greece/minerals/marble/

https://www.litosonline.com/en/article/ancient-greek-marbles-some-still-used-today

A few sources for Greek Sculpture:

Mr. Richard Neer again and Mr.

J. D. Beazley and Bernard Ashmole: Greek Sculpture and Painting to the end of the Hellenistic Period, 1966. Cambridge University Press.

Handbook of Greek Sculpture, edited by Olga Palagia.

Sheila Adam: The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods, 1966, The British School at Athens. Supplementary Volumes No. 3, The Technique of Greek Sculpture in the Archaic and Classical Periods

J. Paul Getty Museum, several papers: Art Historical and Scientific Perspectives on Ancient Sculpture

E. A. Gardner, “The Processes of Greek Sculpture, as Shown by Some Unfinished Statues in Athens”, 1890, The Journal of Hellenic Studies.

H. J. Etienne, 1968, The Chisel in Greek Sculpture: A study of the way in which material, technique and tools determine the design of the sculpture of Ancient Greece, Brill.

Kenneth Lapatin, 2001, Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World, Oxford University Press.