A sentence I often repeat through my posts, but never fully explained. Why is it that Ancient History researchers are so often drawn to the 19th century? Even in the best of chances, if we consider the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century of our era, 1400 years separate our object of study and the dawn of the new era that follows the French Revolution.

There are many good reasons for anyone to love the 19th century. The years between 1801 and 1900 are a period of change in every way. Never before had the world seen such a period of economic and industrial growth. Never before had the population increased in such a fast rhythm. Many people started believing in progress and developing positivist views on Mankind: after the long years of Mannerism, Baroque and Rococo, the brilliance of external appearances shifted towards that of machinery. With aristocracy no longer attempting to be a human work of art, with the old courtly rituals giving place to private life, you see other stars arising: trains, ships, steam engines, agricultural inventions, mechanic looms. The poorer extracts of society, those suffer just as much, perhaps even more so: women and children now work in factories from morning to night, men are trapped within coal mines. One cannot hide the ugly side of progress. But the good side cannot be ignored, either. Medical advances, cultural changes, slow but steady fights for human rights, the 19th century was the central stage of many, not to mention the new styles in Literature and Painting that entirely break from former patterns.

The interest in History also grows. We cannot entirely credit it to the 19th century, of course. Even through the previous centuries, the world started looking back in time, trying to understand where we came from. The Greek and, especially, the Romans, started rising from the ashes of their past empires. Monuments started being observed and sketched. Archaeology begins making itself known. In the 19th century, with the growth of large-scale, worldwide empires, it is natural that many would feel drawn to what they felt would be their natural predecessor, and the studies in Ancient History begin to grow in frequency and importance. Even today, we use the works of Theodor Mommsen, who looked into the History of Ancient Rome in the latter half of the 19th century.

This is also the time when the Medieval fallacy, if you will allow me the expression, begins to grow. The notion of a great cultural setback and of the Dark Ages that follow the fall of the Roman empire develops, as does the idea that Rome was the greatest expression of Mankind’s capacity. It would take a very long time for the Middle Ages to be rehabilitated, for the very word Medieval to lose the negative sense. Nowadays, we know better than that: the world inevitably changed after the fall of Western Rome, but the only reason we may call it a Dark Age is the lack of writings reaching the 21st century. The world did not suddenly awake in the 15th century for the Italian Renaissance. History is a continuum, and without the progress made in the Middle Ages, you would not have the boom that follows. Let’s give the Middle Ages more love and look into Archaeology to understand them, and acknowledge the great works that never made it to our time – this being said by someone who studies Ancient History.

In fact, History is a continuum to an extent where we could say Rome never truly dies: it is merely transformed. Many languages spoken today are essentially deturped Latin. Much of our Law code is a mix of Roman and Visigoth Law. The roads we have today often run through the ancient itineraries of Roman roads. The Ancient World left its mark in fields such as Architecture, Medicine, Astronomy, Philosophy, to an extent it often feels we are not making anything up: we are just improving what they left. This is true in the Middle Ages, especially in the Southern European world, where the memory of Rome was still intensely alive and very much preserved.

A Historian must be honest, and historical honesty involves looking into the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. The 19th century glorified the power of Rome, and undermined the Middle Ages (save certain literary and artistic currents). The former is progress, the latter is a return to Nature. It is not quite so, and virtue lies in balance. But people are a product of their era. 19th century interpretations of Rome were closely connected with the importance to explain the growth and strength of Empires. They looked back and drew their conclusions. And here we are now, looking back at them.

As we enter the Georgian era and the Regency period, during and after the time of the Napoleonic wars, we see the Romans and Greeks knocking on people’s doors. This is reflected even in clothes, especially for women. The wide panniers of the 18th century, the wigs and the rouge, are replaced by a natural look, by Greek designs for dresses that create a Classical silouhette. Houses begin being built with different styles, adding columns of the ancient Roman domus and temple. Themes of Greek and Roman mythology appear in painting and sculpture and become immensely fashionable. Their fascination is immense. I can understand them: my fascination is immense, too. The 19th century ends up being a period when the Greek and Roman ideals are adopted and modernised, and such is made by a society which, in spite of all its differences, is beginning to look a lot like us. The 19th century shaped who we are today in a very determinant manner. Much of its morality and ideas subsist, even if we don’t often realise it. It gives me, the Ancient History researcher, an opportunity to sink into the Classical world, but a renovated Classicism. How can I not love it? Their love was such that now we study something called Classical Reception: how recent eras interpret the Ancient World.

Hence, the Roman world is my spouse. It is what I truly love sinking into and studying, whether we are talking of the Republic or the transition into the Middle Ages. The era to which I am most faithful and always return, and the era which I feel I can contribute to the most. But the 19th century is my lover. An era which retrieves the Ancient World and gives it a new shine (often glossing over the nasty part, that is certain). It is also an era of intense diplomatic efforts on the side of fascinating figures, like Queen Victoria, which makes it immensely appealing. It unites the past and the future to come in a cohesive manner. All is simultaneously new and old. Traditional and progressive. All combined with a mix of polished refinement and raw crudity, almost coarseness, at times. The world moves forth, and the people moved with it, but did not run after practicality. When I look at the 20th century, especially after the First World War, I see a racing world of quickening haste, a speed that never slowed down, at least not until Covid forced us all to take a deep breath. The 19th century allied the haste for the future and the love for the past, a deturped past, that is certain, but an important stone in the path of future Historians. For me, a Historian, that period is particularly appealing: the inevitable march of progress walking hand in hand with a refusal of entirely giving up their core (just look at Queen Victoria!). The 19th century can be a cruel and biased mistress, but it is immensely rewarding, when you sit down to look at it.

And the other Historical eras? They perfectly fit an inevitable truth: that History is carried in Historians’ hearts, as the only way of growing is to know oneself, and the only way for Humanity to grow as a whole is to understand where it came from. They’re all my lovers, in their own ways. Except some are for more occasional conversation, whereas others, I shall walk with them hand in hand and take long walks on the beach.

Images from Wikimedia Commons.

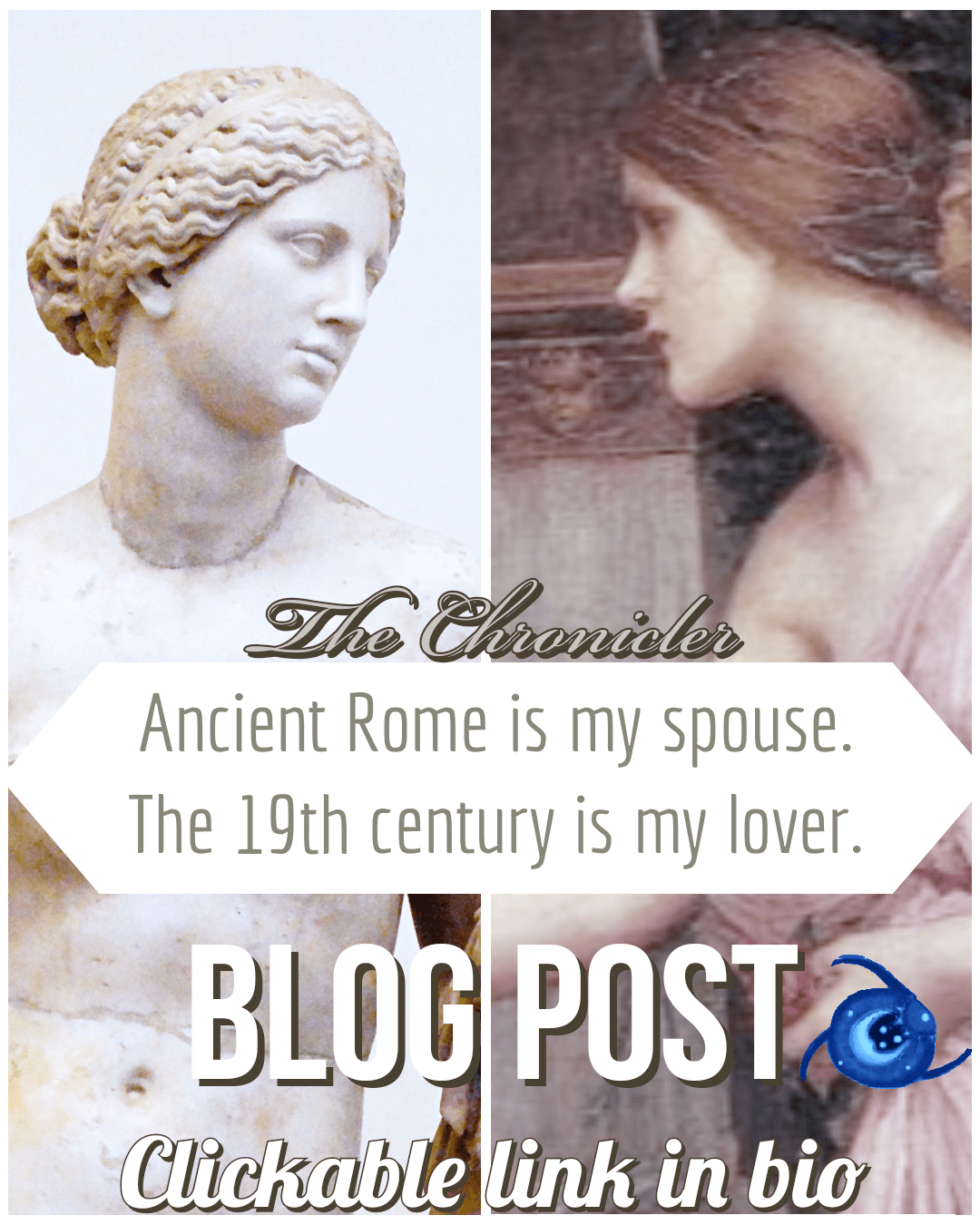

On the left: Aphrodite of Cnidus. Marble. Roman copy of a Greek statue by Praxiteles (4th century BCE).

Link:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File%3ACnidus_Aphrodite_Altemps_Inv8619.jpg?wprov=sfla1

On the right: Psyche Opening the Door into Cupid’s Garden, 1904. By John William Waterhouse.

Link: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File%3APsyche_Opening_the_Door_into_Cupid%27s_Garden.jpg?wprov=sfla1

I agree that there’s nothing more interesting and fascinating than older times, specially the 19 century with all their beauty in art. If I could, I’d live in the 19 century forever!

LikeLike

Same but with 21st century medicine 😂

LikeLike